This essay is an adaptation and simplification of Kenneth M. Wilson’s academic article (2020), reworked to make its insights more accessible for general readers and students who may not have a background in theology or patristic studies.

The short letter of James in the New Testament contains one of the most debated passages in the Bible. In 2:18–20, the writer challenges believers who claim that faith alone—without actions—is enough. For centuries, this passage has been taken to teach that there are two kinds of faith: a true, saving faith that produces love and good works, and a false, “demonic” faith that merely acknowledges facts about God.

Wilson argues this two-faith schema didn’t come from James at all. He traces it to Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE), whose reading was shaped by a church conflict with the Donatists and by the Latin Bible Augustine had in front of him (the Vetus Latina), which lacked key rhetorical markers present in Greek manuscripts of James (Wilson 2020). In short: translation gaps plus polemical context created a powerful interpretation that stuck.

Wilson’s central claim is simple: James isn’t contrasting two different kinds of faith; he’s urging believers within the faith community to live out the faith they already share through merciful action (2:12–13; 2:14–26; 3:1–2). That reads more like a pastoral warning than a metaphysical taxonomy of “true versus false” faith (Johnson 1995, 239–42; Dibelius 1976, 151–55; McKnight 1990).

How Augustine’s Latin Bible Set the Trap

“But someone will say, ‘You have faith, and I have works.’ Show me your faith without your works, and I will show you my faith by my works. You believe that there is one God. You do well. Even the demons believe—and tremble! But do you want to know, O foolish man, that faith without works is dead?” —James 2:18–20

In Greek moral rhetoric there’s a common device called diatribe—a dialogical style where an author imagines an opponent (prosopopoeia), quotes their claim, then responds (Stowers 1981, 119–74). In James 2, the Greek cues are clear: “ἀλλ’ ἐρεῖ τις” (all’ erei tis, “But someone will say…,” 2:18) introduces the interlocutor, and “θέλεις δὲ γνῶναι, ὦ ἄνθρωπε κενέ” (theleis de gnōnai, ō anthrōpe kene, “But do you want to know, O foolish person…,” 2:20) marks James’s rebuttal (cf. Rom. 9:19–20; 1 Cor. 15:35–36; Puskas and Reasoner 2013, 40, 85–86).

Here’s the catch: several Vetus Latina witnesses omit the critical “interlocutor” markers (“but someone will say,” “but do you want to know”) in James 2:18–20. Augustine, especially early in his career, didn’t read Greek and relied on these Latin forms, so he took all the lines as James’s own voice (Thiele 1956–69; Wiles 1995). Because Augustine’s Latin Bible lacked these linguistic guideposts, the conversation collapsed into a monologue and created fertile soil for later confusion. His misreading of James as the speaker forced him to grapple with a tangled web of demonology and soteriology—a problem the text itself never posed. That’s how “even the demons believe” moved from the mouth of the imaginary opponent into James’s mouth—creating a theological problem Augustine felt obliged to solve.

The Donatist Fight and Augustine’s “Demonic Faith”

When Augustine opposed the Donatists—a rigorist North African Christian movement that broke communion with the wider church—he repeatedly cited James 2:18–20 (ca. 404–415). The Donatist schism arose in the wake of Diocletian’s persecution, when some clergy were accused of having handed over sacred texts to Roman officials. The Donatists argued that these traitorous bishops forfeited their spiritual authority, and that the sacraments administered by them were invalid. Augustine, serving as bishop of Hippo, regarded this as a threat to the unity and catholicity of the Church, insisting that the moral failings of clergy did not nullify the grace of the sacraments. His struggle with them was not only theological but deeply ecclesiological—a battle over what it meant to belong to the one body of Christ amid moral compromise and political pressure.

In this context, Augustine began to argue that the Donatists believed but lacked charity and unity; therefore, their “faith” was like that of demons and did not save (Augustine, Serm. 162A.4, 7; Tract. Ev. Jo. 6.21). He even subtly changed the hypothetical interlocutor’s phrase “you do well” (kalōs poieis) to “you believe well” (bene credis), turning an ethical commendation into a doctrinal statement (Augustine, Serm. 162A; Wilson 2020).

By 411–413, he was pairing James 2 with Galatians 5:6 (“faith working through love”) as an interpretive key: true faith works through love; demonic faith merely assents and fears (Serm. 16A.11; Serm. 53.10–11). This marks the first explicit, systematic articulation of two kinds of faith in the Christian tradition (Johnson 1995, 138; Wilson 2020).

Augustine Codifies “Two Kinds of Faith”

In a 413 sermon (Serm. 53.10–11), Augustine draws the line between:

- Our faith—which purifies the heart and works through love (Gal. 5:6).

- Demonic faith—which recognizes truth (“You are the Son of God”) but lacks love and thus condemns (Mark 1:24; Luke 4:34).

He frames it vividly in Latin:

“Et fides daemonum credendo est, sed timendo; fides Christianorum credendo est, sed amando.” (“The faith of demons is by believing and fearing; the faith of Christians is by believing and loving.”)

This brief line captures Augustine’s moral contrast between fear and love, a rhythm that would echo through his later writings on grace and charity.

He later adds a Latin prepositional distinction: believing that Christ is (even demons do this) versus believing in Christ (trusting, hoping, loving)—the latter alone saves (Serm. 144.2). Greek usage, however, doesn’t sustain this hard divide (Botha 1987; Schnackenburg 1968–82). Nevertheless, the rhetorical move allowed Augustine to argue that Donatists had the wrong kind of faith.

Within a century, the Augustinian template spread: Severus of Antioch, Euthalius’s scholia, later John Damascene, and then medieval commentators read James 2 through the “true versus demonic faith” filter. Bede leans heavily on Augustine (Bede, Ep. Cath. on Jas 2; Augustine, Ep. 167). The interpretive echo chamber was established.

What Other Ancient Christians Actually Said

Before Augustine, references to James 2:19 are sparse and non-programmatic:

- Jerome cites “even devils believe and tremble” as a jab (knowledge alone isn’t enough), not as a taxonomy of faith (Jerome, Adv. Jov. 2.2).

- John Chrysostom cites James but never spins the idea of “demonic faith.”

- Cyril of Alexandria treats faith without obedience as insufficient for intimacy with God but does not posit “false faith versus true faith” (Cyril, Comm. Jo. 15.7; Russell 2000).

The two-faith schema is Augustine’s innovation, and does not appear in any extant patristic readings for nearly the first four hundred years of church history (Wilson 2020).

Many Modern Translations Still Lean Augustinian

Most English Bibles end quotation marks after James 2:18a and treat 2:19 as James’s own voice. That structure forces “even the demons believe” into James’s mouth and nudges readers toward Augustine’s two-faith solution. Richard Weymouth’s translation is a notable outlier, allowing the interlocutor to speak through verse 19 (Weymouth 1903; Wilson 2020).

Scholars have long recognized the rhetorical cues: the “someone will say…” in 2:18 and the adversative “but do you want to know, O foolish person…” in 2:20 mark the switch back to the author (Mayor 1897, 93; Donker 1981, 234–35; Burchard 2000, 124). Allowing the objector to speak through 2:19 fits the diatribe form (Stowers 1981) and removes the need for a two-faith fix.

Reading 2:18–20 with the Interlocutor Restored

If we let the imagined opponent talk through verse 19, his point is that faith and works are independent. He taunts: “Show me your faith without works; I’ll show you mine by works” (an impossible challenge), then illustrates, “You affirm monotheism—good. Demons affirm it too—yet only shudder.” The same belief appears with different outcomes, so (he argues) belief doesn’t necessarily entail works (Dibelius 1976, 154–55; Verseput 1997). Thus we see that the very claim James derided in this passage became a theological foundation for Augustine in his contention with the Donatists.

James’s reply (v. 20) doesn’t try to prove that good works reveal “true faith” or that demons have the “wrong kind of faith.” He calls the argument empty and pivots: when God judges His people (2:12–13; 3:1–2; 5:8–9), faith left idle is useless—“as good as dead”—because judgment evaluates works (2 Cor. 5:10; Rom. 14:10; Col. 3:22–24). This is a family address to “brothers and sisters,” not boundary-policing about who’s “fake” (Johnson 1995, 240; Ellis 2015; Yinger 1999).

Also note the Greek: kalōs poieis (“you do well”) in 2:19 naturally means doing good, not sarcasm (“well, good for you”). Elsewhere in the LXX and NT, kalōs poiein denotes doing good, not irony (Luke 6:27; Matt. 12:12; Lev. 5:4 LXX; Isa. 1:17 LXX). The sarcastic reading is driven more by Augustine’s framework than by actual usage (Frankemölle 1994).

The Immediate Context in James

James brackets 2:18–19 with two inclusios emphasizing the same thesis: faith apart from works is barren or dead (2:14–17; 2:20–26) (Frankemölle 1994, 429; McKnight 1990). The surrounding warnings are all in-house:

- “So speak and act as those who are to be judged…” (2:12–13)

- “We who teach will be judged more strictly” (3:1–2)

- “The Judge is standing at the door… do not grumble, brothers and sisters” (5:8–9)

This matches Second Temple Jewish expectations that God judges His people—often temporally (discipline/reward), not as a heaven-or-hell verdict (Deut. 32:36 LXX; Eccl. 12:14; Heb. 10:30; 1 Pet. 1:17; Yinger 1999, 90–96). James’s focus, then, is not “true versus false faith,” but useful versus useless faith at the coming judgment of works.

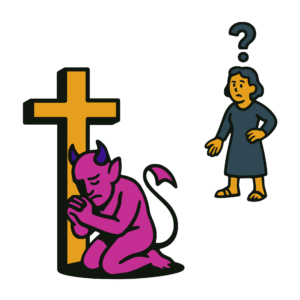

Why Augustine’s Reading Endured

Augustine’s interpretive model offered later readers a way to smooth over the apparent tension between Paul and James—but at a tragic cost. His effort to protect the unity and purity of the Church ironically mirrored the very schism he condemned in the Donatists. In striving to preserve the body of Christ, he drew new lines within it. The logic that once divided Donatists from Catholics soon became a permanent feature of Christian thought, allowing generations of believers to weaponize the same division against one another—turning theological nuance into grounds for exclusion.

In this ironic reversal, the harmonization of Paul and James became less about integration and more about boundary-making. Augustine’s formulation—faith that saves versus faith that damns—offered an elegant symmetry on paper but fractured Christian community in practice. The idea of “demonic faith” gave later theologians permission to dismiss dissenters as spiritually defective, perpetuating the very mutilation of the Body of Christ Augustine once decried. His interpretive brilliance thus carried within it a kind of sorrowful genius: a cure that prolonged the illness it sought to heal (Dibelius 1976, 152–55; Johnson 1995, 138; Wilson 2020).

A Text-First Reading

Restoring the dialogue signals, the logic is tight:

- Interlocutor (2:18–19): Faith and works can be separate; look at demons!

- James (2:20–26): That argument is foolish. Faith left idle is useless when God judges His people; therefore, live your faith in merciful action (2:12–13; 2:15–16; 3:1–2; 5:8–9).

No need to invent two ontologically distinct “faiths.” James’s pastoral message lands where he aims: faith is meant to be lived (Watson 1993; Verseput 1997; Popkes 2001).

The Lesson Learned

This entire episode serves as a cautionary tale that good intentions do not absolve harmful outcomes. Augustine, seeking to heal a Church torn by schism, became ensnared by the very logic of division he fought to eradicate. His passion for unity led him to misread James and construct a theology that would itself divide believers for more than sixteen centuries—a sobering reminder that even the brightest theological minds can mistake zeal for truth when the word of God is handled carelessly and the end is allowed to justify the means.

References

- Adamson, James. 1976. The Epistle of James. NICNT. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Allison, Dale C., Jr. 2013. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle of James. ICC. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

- Augustine of Hippo. 1990–1997. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century. Translated by Edmund Hill. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press.

- Botha, E. 1987. “Pisteuō in the Greek New Testament: A Semantic-Lexicographical Study.” Neotestamentica 21: 225–40.

- Burchard, Christoph. 2000. Der Jakobusbrief. HNT 15.1. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Cyril of Alexandria. Quoted in Norman Russell. 2000. Cyril of Alexandria. The Early Church Fathers. New York: Routledge.

- Dibelius, Martin. 1976. James: A Commentary on the Epistle of James. Revised by Heinrich Greeven. Translated by Michael A. Williams. Hermeneia. Philadelphia: Fortress.

- Donker, Christian E. 1981. “Der Verfasser des Jak und sein Gegner: Zum Problem des Einwändes in Jak 2,18–19.” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 72: 227–40.

- Ellis, Nicholas. 2015. The Hermeneutics of Divine Testing: Cosmic Trials and Biblical Interpretation in the Epistle of James and Other Jewish Literature. WUNT 2/396. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Frankemölle, Hubert. 1994. Der Brief des Jakobus. 2 vols. ÖTK 17. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus.

- Johnson, Luke Timothy. 1995. The Letter of James. AB 37A. New York: Doubleday.

- Mayor, Joseph B. 1897. The Epistle of St. James. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan.

- McKnight, Scot. 1990. “James 2:12a.” Westminster Theological Journal 52: 355–64.

- Puskas, Charles, and Mark Reasoner. 2013. The Letters of Paul: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

- Russell, Norman. 2000. Cyril of Alexandria. The Early Church Fathers. New York: Routledge.

- Schnackenburg, Rudolf. 1968–1982. The Gospel According to John. Translated edition of HThKNT. New York: Herder & Herder.

- Stowers, Stanley K. 1981. The Diatribe and Paul’s Letter to the Romans. SBLDS 57. Chico, CA: Scholars Press.

- Thiele, Walter, ed. 1956–1969. Epistulae Catholicae. Vetus Latina 26.1. Freiburg: Herder.

- Verseput, Donald. 1997. “Reworking the Puzzle of Faith and Deeds in James 2:14–26.” New Testament Studies 43: 97–115.

- Watson, Duane. 1993. “James 2 in Light of Greco-Roman Schemes of Argumentation.” New Testament Studies 39: 94–121.

- Weymouth, Richard F. 1903. The New Testament in Modern Speech. Revised edition. London: James Clarke.

- Wilson, Kenneth M. 2020. “Reading James 2:18–20 with Anti-Donatist Eyes: Untangling Augustine’s Exegetical Legacy.” Journal of Biblical Literature 139 (2): 385–407. https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1392.2020.8.

- Wiles, James. 1995. A Scripture Index to the Works of St. Augustine in English Translation. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Yinger, Kent L. 1999. Paul, Judaism, and Judgment According to Deeds. SNTSMS 105. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.